Western civilization really is at risk from Muslim extremists.

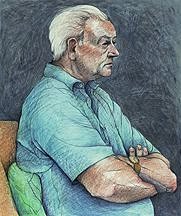

By Sam Harris

SAM HARRIS is the author of "The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason." His next book, "Letter to a Christian Nation," will be published this week by Knopf. samharris.org.

September 18, 2006

TWO YEARS AGO I published a book highly critical of religion, "The End of Faith." In it, I argued that the world's major religions are genuinely incompatible, inevitably cause conflict and now prevent the emergence of a viable, global civilization. In response, I have received many thousands of letters and e-mails from priests, journalists, scientists, politicians, soldiers, rabbis, actors, aid workers, students — from people young and old who occupy every point on the spectrum of belief and nonbelief.

This has offered me a special opportunity to see how people of all creeds and political persuasions react when religion is criticized. I am here to report that liberals and conservatives respond very differently to the notion that religion can be a direct cause of human conflict.

This difference does not bode well for the future of liberalism.

Perhaps I should establish my liberal bone fides at the outset. I'd like to see taxes raised on the wealthy, drugs decriminalized and homosexuals free to marry. I also think that the Bush administration deserves most of the criticism it has received in the last six years — especially with respect to its waging of the war in Iraq, its scuttling of science and its fiscal irresponsibility.

But my correspondence with liberals has convinced me that liberalism has grown dangerously out of touch with the realities of our world — specifically with what devout Muslims actually believe about the West, about paradise and about the ultimate ascendance of their faith.

On questions of national security, I am now as wary of my fellow liberals as I am of the religious demagogues on the Christian right.

This may seem like frank acquiescence to the charge that "liberals are soft on terrorism." It is, and they are.

A cult of death is forming in the Muslim world — for reasons that are perfectly explicable in terms of the Islamic doctrines of martyrdom and jihad. The truth is that we are not fighting a "war on terror." We are fighting a pestilential theology and a longing for paradise.

This is not to say that we are at war with all Muslims. But we are absolutely at war with those who believe that death in defense of the faith is the highest possible good, that cartoonists should be killed for caricaturing the prophet and that any Muslim who loses his faith should be butchered for apostasy.

Unfortunately, such religious extremism is not as fringe a phenomenon as we might hope. Numerous studies have found that the most radicalized Muslims tend to have better-than-average educations and economic opportunities.

Given the degree to which religious ideas are still sheltered from criticism in every society, it is actually possible for a person to have the economic and intellectual resources to build a nuclear bomb — and to believe that he will get 72 virgins in paradise. And yet, despite abundant evidence to the contrary, liberals continue to imagine that Muslim terrorism springs from economic despair, lack of education and American militarism.

At its most extreme, liberal denial has found expression in a growing subculture of conspiracy theorists who believe that the atrocities of 9/11 were orchestrated by our own government. A nationwide poll conducted by the Scripps Survey Research Center at Ohio University found that more than a third of Americans suspect that the federal government "assisted in the 9/11 terrorist attacks or took no action to stop them so the United States could go to war in the Middle East;" 16% believe that the twin towers collapsed not because fully-fueled passenger jets smashed into them but because agents of the Bush administration had secretly rigged them to explode.

Such an astonishing eruption of masochistic unreason could well mark the decline of liberalism, if not the decline of Western civilization. There are books, films and conferences organized around this phantasmagoria, and they offer an unusually clear view of the debilitating dogma that lurks at the heart of liberalism: Western power is utterly malevolent, while the powerless people of the Earth can be counted on to embrace reason and tolerance, if only given sufficient economic opportunities.

I don't know how many more engineers and architects need to blow themselves up, fly planes into buildings or saw the heads off of journalists before this fantasy will dissipate. The truth is that there is every reason to believe that a terrifying number of the world's Muslims now view all political and moral questions in terms of their affiliation with Islam. This leads them to rally to the cause of other Muslims no matter how sociopathic their behavior. This benighted religious solidarity may be the greatest problem facing civilization and yet it is regularly misconstrued, ignored or obfuscated by liberals.

Given the mendacity and shocking incompetence of the Bush administration — especially its mishandling of the war in Iraq — liberals can find much to lament in the conservative approach to fighting the war on terror. Unfortunately, liberals hate the current administration with such fury that they regularly fail to acknowledge just how dangerous and depraved our enemies in the Muslim world are.

Recent condemnations of the Bush administration's use of the phrase "Islamic fascism" are a case in point. There is no question that the phrase is imprecise — Islamists are not technically fascists, and the term ignores a variety of schisms that exist even among Islamists — but it is by no means an example of wartime propaganda, as has been repeatedly alleged by liberals.

In their analyses of U.S. and Israeli foreign policy, liberals can be relied on to overlook the most basic moral distinctions. For instance, they ignore the fact that Muslims intentionally murder noncombatants, while we and the Israelis (as a rule) seek to avoid doing so. Muslims routinely use human shields, and this accounts for much of the collateral damage we and the Israelis cause; the political discourse throughout much of the Muslim world, especially with respect to Jews, is explicitly and unabashedly genocidal.

Given these distinctions, there is no question that the Israelis now hold the moral high ground in their conflict with Hamas and Hezbollah. And yet liberals in the United States and Europe often speak as though the truth were otherwise.

We are entering an age of unchecked nuclear proliferation and, it seems likely, nuclear terrorism. There is, therefore, no future in which aspiring martyrs will make good neighbors for us. Unless liberals realize that there are tens of millions of people in the Muslim world who are far scarier than Dick Cheney, they will be unable to protect civilization from its genuine enemies.

Increasingly, Americans will come to believe that the only people hard-headed enough to fight the religious lunatics of the Muslim world are the religious lunatics of the West. Indeed, it is telling that the people who speak with the greatest moral clarity about the current wars in the Middle East are members of the Christian right, whose infatuation with biblical prophecy is nearly as troubling as the ideology of our enemies. Religious dogmatism is now playing both sides of the board in a very dangerous game.

While liberals should be the ones pointing the way beyond this Iron Age madness, they are rendering themselves increasingly irrelevant. Being generally reasonable and tolerant of diversity, liberals should be especially sensitive to the dangers of religious literalism. But they aren't.

The same failure of liberalism is evident in Western Europe, where the dogma of multiculturalism has left a secular Europe very slow to address the looming problem of religious extremism among its immigrants. The people who speak most sensibly about the threat that Islam poses to Europe are actually fascists.

To say that this does not bode well for liberalism is an understatement: It does not bode well for the future of civilization.

Copyright 2006 Los Angeles Times